This post is a bit dated....ok, it’s very dated. I wrote it in February (when I first thought of creating my own blog), right after Governor Rajan announced the withdrawal of the Export Credit Refinance (ECR) facility. Then followed five months of procrastination. Fast toward to day - am finally posting it.

This post is dedicated to understanding the erstwhile ECR facility - it’s concept, effectiveness and finally, the rationale behind its discontinuation.

ECR 101

Export Credit Refinance or ECR was a facility provided by the RBI to banks on the basis of their eligible outstanding rupee export credit (both at pre-shipment and post shipment phases). The quantum of the facility was fixed from time to time depending upon the stance of RBI’s monetary policy. ECR was repayable on demand or the expiry of a maximum term of 180 days. It was available at an interest rate = the Repo rate under the Liquidity Adjustment Facility (LAF). To avail of this facility, the borrowing bank had to provide a Demand Promissory Note (essentially a signed legal document where the maker i.e. bank unconditionally promised to pay a certain amount of money on demand to the holder i.e. RBI) along with other documents.

Lets take a real life example. Suppose the amount of ECR a bank could avail of was fixed at 50% of eligible export credit. This means that a bank that needed liquidity and had extended export credit of Rs. 100 crores, could go to the RBI and get Rs. 50 crores of refinance at the prevailing repo rate in exchange for a demand promissory note and other documentation.

Purpose of ECR

The key purpose of ECR was two-fold:

- It was a tool to augment liquidity for banks. In addition to borrowing at the repo rate under the LAF, banks with eligible export loan books could now also use the ECR facility to get funds at the same repo rate.

- It was also a mechanism to encourage the flow of credit to the export sector.

While the ECR helped achieve these objectives to an extent, its effectiveness in doing so has been limited. Lets understand why.

How effective was ECR really?

Lets first examine the effectiveness of ECR as a tool to augment liquidity for banks.

It’s well known that ECR was never the banks’ preferred instrument to meet liquidity requirements. The facility was rarely fully utilized. There are a couple of reasons for this –

- ECR was useful only for banks with large export credit portfolios that needed to augment liquidity. A bank that did not have much export credit yet needed liquid funds, did not benefit from ECR. For example, PSU banks often had large export loan books, but tended to be comfortable on the liquidity front. Private or foreign banks on the other hand, may have need liquidity support, but may not have had an adequately large export credit portfolio to effectively utilise the ECR facility.

- LAF Repo is the banks’ preferred borrowing tool to meet short-term liquidity needs. It’s easier, faster, independent of the size of the export loan book and does not require the kind of documentation that ECR did.

Next, let us look at the effectiveness of ECR as a tool to encourage credit flow to the export sector.

- While ECR did enhance the flow of credit to the export sector to an extent, its impact was limited as could be deduced from the mostly unutilized limits of the ECR facility. As we discussed above, banks tended to shy away from utilizing ECR to meet their liquidity requirements. Consequently, ECR’s role in increasing credit flow to the export sector appears to have been stronger in theory than in practice.

- For exporters what is key as far as export credit is concerned is the cost of funds. An increase in the ECR limit did not always translate into a proportional decrease in the loan rates offered to exporters, which are based on bank base rates (the minimum rate of interest that a bank charges from its customers) and take many other factors into account.

Bottom-line, it is safe to say that the effectiveness of the ECR facility in achieving its stated objectives was limited.

Move away from ECR was in the works already...

The Urjit Patel Committee (Urjit Patel is the Deputy Governor of the RBI) set up to review the RBI’s monetary policy framework, recommended last year that the RBI should move away from sector-specific refinance towards a more generalized provision of system liquidity without preferential access to any particular sector or entity. This would help improve the transmission of policy impulses across the interest rate spectrum and improve efficiency in cash management.

This recommendation is not new. It is widely accepted that as money markets mature, emphasis on direct measures of monetary policy (such as sector-specific refinance) should weaken, and indirect policy instruments (such as LAF, Open market operations) should take centre-stage. Such a shift in emphasis in turn engenders further maturity and development of markets. It’s a virtuous cycle.

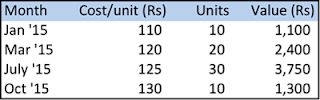

Consequently, the RBI has wanted to move away from ECR for some time. Under Governor Rajan however, this goal finally came to fruition. In the monetary policy statement of June 2014, funds available under ECR were reduced from 50% to 32% of eligible export credit; in Oct 2014, they were cut to 15%; the ECR facility was finally withdrawn in Feb 2015.

Conclusion

The decision to withdraw the ECR facility was eminently prudent. This facility was never the best tool to achieve either of its stated objectives.